Niemeyer, Le Corbusier and the United Nations Headquarters Challenge

The year 1945 marked a critical moment in global history. World War II came to an end, and with the declaration of peace, a wave of euphoria and optimism flooded the streets of the world’s nations. This atmosphere of hope and renewal inspired the creation of the United Nations (UN) in the same year. This new international entity was established with a clear objective: to maintain peace and promote cooperation among nations, a purpose that was considered fundamental to avoid future devastating conflicts.

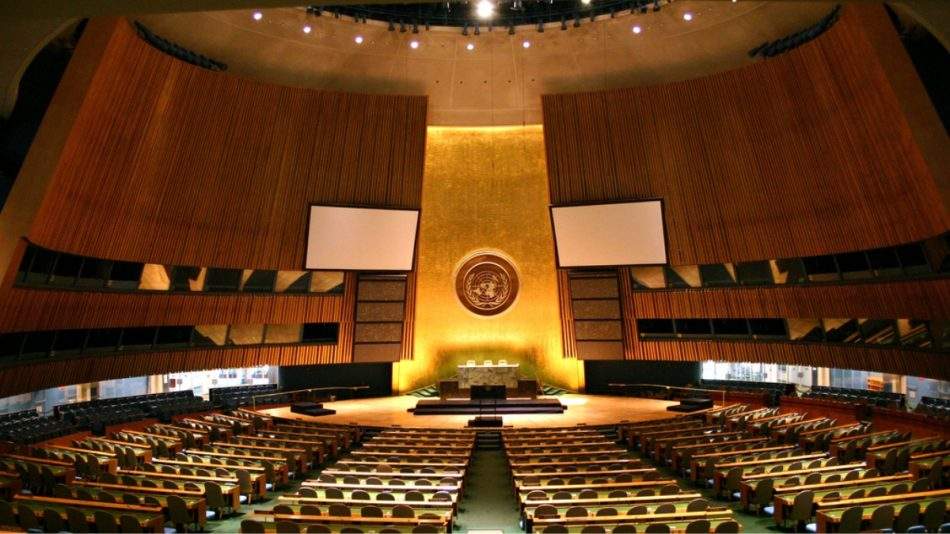

The choice of the UN headquarters was a matter of great importance and symbolism. It was decided that vibrant New York City would be the central location to house this institution. But, creating a headquarters for the UN was no ordinary task. It required an extraordinary architectural project that reflected the vision of unity and collaboration of the nations of the world. The UN sought the help of internationally renowned architects whose talent and skill would be instrumental in bringing this ambitious project to life.

Selecting the architects was no easy task. It required an international team that could work together to conceive and execute a unique vision. What was interesting about this challenge was that the architects chosen were known for their strong personalities and their tendency to exert total control over their architectural designs and, in some cases, over the destinies of their respective countries. These inflated egos were a common trait in the architectural profession, but in this project, they would have to learn to coexist in the same space and collaborate on a single purpose: to create the United Nations headquarters.

Eleven renowned architects from different corners of the world joined the project. Each brought a unique perspective and personal vision, which posed an additional challenge: finding common ground among these brilliant architects with different approaches and styles. Collaboration on this project would not only be a creative challenge, but also compelling proof of the possibility of achieving world peace through cooperation and mutual understanding.

The leadership of the team fell to Wallace K. Harrison, an American architect with an architectural background that had developed in Paris. During his time in the City of Light, Harrison had developed a deep admiration for Le Corbusier, an influential Swiss-French architect known for his pioneering work in modernism. Harrison played a crucial role in this monumental effort, and his experience on notable projects such as Rockefeller Center made him a wise choice to lead this international team.

However, the task of leading a group of architects with inflated egos was not easy. Harrison not only had to manage the execution of the project, but also harness his generosity and diplomatic skills to maintain team cohesion. Among all the invited architects, Harrison showed a special concern for Le Corbusier, who was already known for his inflexibility in terms of his ideas and his personal approach to projects.

Le Corbusier, whose real name was Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, was an iconic figure in the world of architecture. His work had revolutionized the profession with concepts such as the pilotis towers and his vision of the city of the future. He had an impressive career behind him and presented his ideas in a coherent and convincing manner. His fame and authority made him an obvious candidate to lead the United Nations Headquarters project. In fact, Le Corbusier referred to himself as the “master of the project,” positioning the other architects as his collaborators rather than his equals. This posed a significant challenge for Harrison, who had to skillfully balance control and respect for egos within the group.

Oscar Niemeyer, another renowned architect who joined the project, had gained international recognition, most notably for his Brazilian Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair. Despite his youth and relative inexperience compared to some of his colleagues, Niemeyer was considered one of the most original talents of his generation. Although there were concerns at first because of his communist affiliation, the architects working on the project found Niemeyer accessible and easy to communicate with. His fresh approach and creative perspective made him a valuable member of the team.

As the United Nations Headquarters project progressed, Le Corbusier’s ideas began to gain priority, either because of their intrinsic merit or because of the respect in which he was held. However, not all architects fully supported his vision, especially with regard to the construction of a large tower at the center of the site. Oscar Niemeyer was one of those who initially hesitated to voice his disagreements and chose to align himself with the master’s ideas, at least initially.

As the development of the project progressed, an unexpected situation altered the course of the collaboration. Le Corbusier had to leave suddenly to attend to business in his office in France, which required a temporary absence of his leadership. This circumstance marked a change in the direction of the project and presented an additional challenge. In Le Corbusier’s absence, Harrison intended to elevate the contributions of the other architects and give them more room to influence the design.

However, Niemeyer, despite his previous involvement, showed little enthusiasm and participation in the meetings at that time. Understanding the circumstances, Harrison decided to call a specific meeting with Niemeyer, expressing his expectation that the Brazilian architect would submit a proposal for the project, as this was the main purpose behind his invitation to the team. Despite his initial misgivings and respect for Le Corbusier, Niemeyer eventually agreed to Harrison’s request, although he offered a cautionary comment before embarking on his proposal, saying: “You will create confusion”.

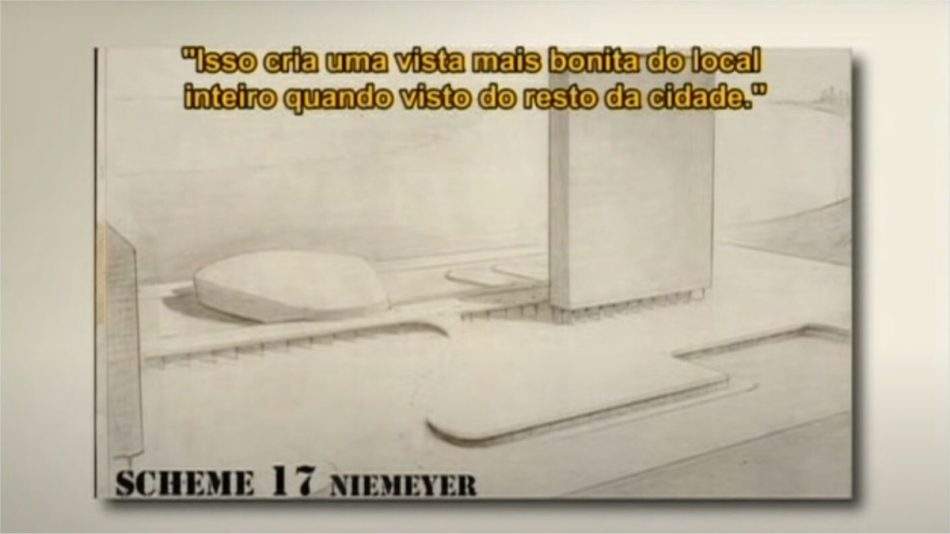

The result of this request was Proposal 17, a vision that differed substantially from Le Corbusier’s. Niemeyer proposed dividing the plot into three distinct buildings and creating an open area between the city boundary and the river. This idea quickly gained the support and approval of both Harrison and the majority of the group. Proposal 17, with its focus on openness and architectural diversity, offered an alternative vision to Le Corbusier’s more monolithic vision and sparked a thorough discussion about the direction of the project.

However, Le Corbusier’s absence did not last long. Upon his return from Paris, the Swiss-French architect was accompanied by Vladimir Bodiansky, a former colleague who came on board to support and strengthen his ideas. Up to that point, Proposition 23, designed by Le Corbusier, consisted of a substantial block intended to be the dominant central structure on the site, which would house both the conference hall and the UN Council.

The return of Le Corbusier and the introduction of Bodiansky to the team marked a significant change in the dynamics of the project. Tensions began to rise when Le Corbusier learned that the young Brazilian’s proposal had been selected. Visibly uncomfortable, Le Corbusier argued that the entire block should maintain a single, pure and simple form, which raised several criticisms of Niemeyer’s project.

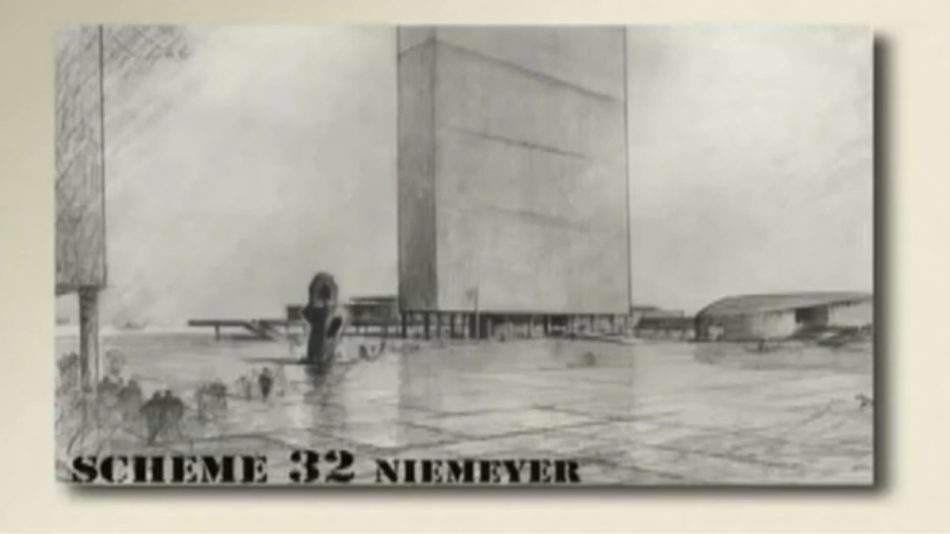

In response to these tensions, Niemeyer chose to absent himself from the next meeting, citing a cold as an excuse. However, his absence was temporary, and in subsequent meetings, he presented a revised proposal that incorporated ideas from other architects, including Le Corbusier. This new proposal, known as Proposal 32, represented a meeting point between the visions of the various architects and received the support of the majority of the group.

However, Le Corbusier still insisted on his original proposal and his vision of a single, simple block at the center of the site. The final confrontation between Le Corbusier and Niemeyer was about to take place, and the crucial moment was approaching. The decision as to which design would be implemented was the responsibility of Harrison, who had a pivotal role in the process.

When the time came, Harrison, with impeccable diplomatic skill, announced the decision, stating, “Taking into account the challenges and the time available to us, I have come to the conclusion that the only one of these sketches that is completely satisfactory is a concept originally proposed by Le Corbusier and developed by Oscar Niemeyer”. Harrison presented this decision in order to maintain harmony in the group and move the project forward efficiently.

Le Corbusier thanked Harrison for his statement in public, expressing his satisfaction with what he had heard. Outwardly, it appeared that Le Corbusier had accepted the decision, but privately, his ego had suffered a major blow. The confrontation between two giants of modern architecture had reached its conclusion, but tensions remained, but in a more disguised form.

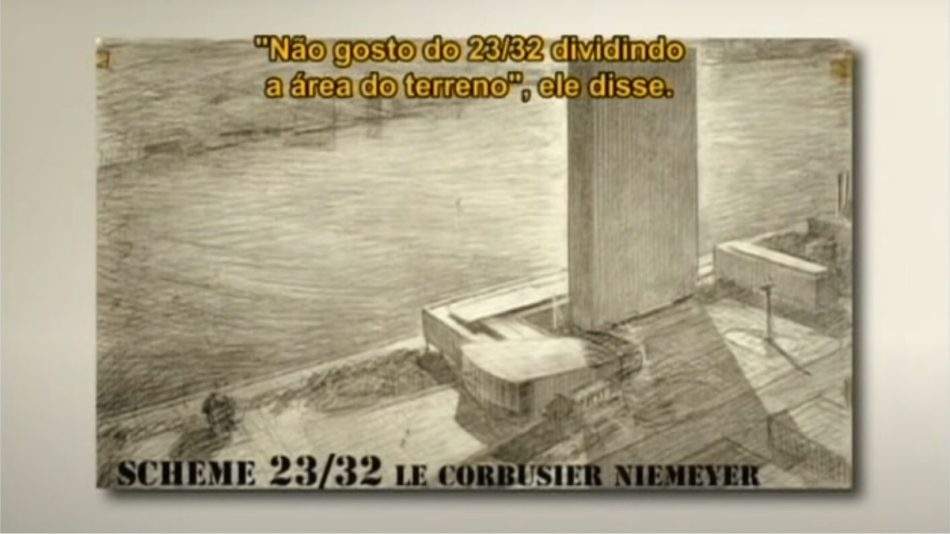

The turning point came when Le Corbusier suggested to Niemeyer that the ensemble be placed in the center of the site rather than in the plaza, highlighting a notable difference in their hierarchical visions of the project. Despite his frustration, the young Brazilian architect resisted this proposal, leading to the selection of a combination of the two architects’ ideas, known as Proposal 23/32. The final vision reflected a blend of their creative perspectives and posed a compromise solution to meet the expectations of both sides.

However, disagreement persisted in the background, and the differences between Le Corbusier and Niemeyer over the direction of the project were never fully resolved. During a post-decision lunch, Le Corbusier simply said, “You were generous”. Although he did not provide further details, Niemeyer understood this to be a reference to the United Nations project and the choice of his proposal.

In the last years of his life, in an interview, Niemeyer revealed that, if it were in the present day, he would not have accepted Le Corbusier’s idea, as he never believed it was the best choice for the project. However, given his youth and respect at the time, he chose to comply and participate in the execution of the project according to the guidelines of combining his ideas and those of Le Corbusier.

This tumultuous process, marked by bruised egos and deep disagreements, culminated in the inauguration of the United Nations Headquarters in New York on October 24, 1949. This event brought together people from diverse cultures and nations, illustrating that respecting and embracing pluralism is often challenging, but ultimately rewarding. The United Nations Headquarters became a symbol of international cooperation and a beacon of hope in a world yearning for peace and unity.

- Architects: Harrison Wallace Kirkman, Gaston Brunfaut, Liang Seu-Cheng, Sven Markelius, Oscar Niemeyer, Howard Robertson, Argyle Soilleux Garnet, Julio Vilamajo, Nikolai Bassov, Ernest Cormier, Le Corbusier.

- Year of construction: 1949–1952

- Height: 168 m

- Floors: 39

- Cost: $65,000,000 USD

- Location: New York, United States.

Comments

We are interested in your opinion, please leave us a comment